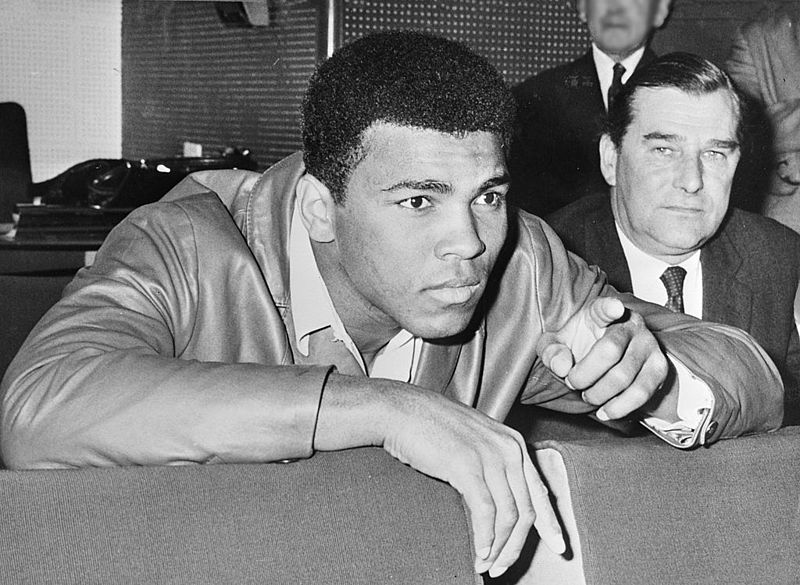

Remembering Muhammad Ali: Asiatic Black Man

With the passing of Muhammad Ali – boxing’s greatest pugilist, most electric persona, and fiercest champion for racial justice – we have also witnessed another step in his long transition from controversial social activist to palatable American hero. Like his contemporary and friend, Malcolm X, who was celebrated by the U.S. government through a commemorative postage stamp in 1998 despite his life as a stringent critic of American racism, capitalism, and foreign policy, Ali’s place as a radical political figure has slowly eroded alongside his ailing health. Central to this revisionist narrative is how we remember his decision to resist the draft during the height of the Vietnam War.

His refusal, which was rooted in his religious faith and conversion to the Nation of Islam (NOI), has been decontextualized and seen as one man’s principled stand against war. Its significance is often framed in the context of the emerging antiwar movement. Thus, in most recollections of Ali’s life and legacy since his passing, the NOI is a mere footnote. Even those who have stressed his significance as an ambassador for Islam, have coupled this by noting the declining influence of the Nation of Islam in contemporary American Muslim and black communities.

When Muhammad Ali had his draft status reclassified in February 1966, he was asked about the decision by Bob Lipsyte.1 “Clay would make no comment on the war itself, or America’s commitment in Vietnam,” the journalist remembered.”2 Then, “all of [a] sudden he hit the note.” Ali turned to a reporter and said: “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong.” Lipsyte later called it “the moment for Ali. For the rest of his life he would be loved and hated for what seemed like a declarative statement, but what was, at the time, a moment of blurted improvisation.”3 The following year, the heavyweight champion refused induction into the Army and stepped into a long legal battle which would last until 1971, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction for draft evasion on a technicality.

But the lesser-quoted second-half of Ali’s famous comment is crucial to understanding his resistance to the war. The Vietnamese, he clarified, were “considered . . . Asiatic black people and I don’t have no fight against black people.”4 He was not merely opposed to the Vietnam War in terms of American interventionism. Nor was his stance analogous to that made by other religious Conscientious Objectors (COs) such as Quakers and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Citing the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Qur’an, Ali claimed he could not fight a war “on the side of nonbelievers.” His stand in Vietnam was foremost an articulation of anticolonial black nationalism which emphasized solidarity with other Third World people. It was also not a racially essentialist argument, but one which understood American involvement in Southeast Asia as an expression of global white supremacy and settler-colonialism. In fact, a few years later, the Nation of Islam’s paper, Muhammad Speaks, even proposed that Irish Catholics’ struggle against the British could be understood in similar terms.5

From the moment Ali chose to resist the draft, interpretations differed dramatically. For many African Americans, it meant Ali was unwilling to fill the prescribed role of the “credit-to-his-race” athlete embodied by former heavyweight champion Joe Louis. Many boxing critics mistook Ali’s actions as part of a broader youth rebellion personified by floppy hair, drugs, and sexual lasciviousness. Sportswriter Jimmy Cannon wrote that “Clay is part of the Beatles’ movement. He fits in with famous singers no one can hear and punks riding motorcycles with iron crosses pinned to their leather jackets and Batman and the boys with their long dirty hair and girls with the unwashed look and the college kids dancing naked at secret proms held in apartments and the revolt of students who get a check from dad every first of the month and the painters who copy the labels off soup cans and the surf bums who refuse to work and the whole pampered style-making cult of the bored young.”6 And for young people who had witnessed over a half million of their peers inducted in the years 1966 and 1967, Ali was the figurehead of the nascent antiwar movement. But, as Jeffrey Sammons points out, in doing so these mostly-white “students seemed willing to overlook his positions on integration, intermarriage, drugs, and the counterculture,” all of which stood in stark contrast to the emerging hippie ethos.7

Despite being commonly referred to as “Black Muslims” (a phrase which persists today), members of the Nation of Islam rejected this identity, considering themselves an “Asiatic” people. This did not mean that they rejected blackness; to the contrary, the group’s insistence on using the phrase “so-called Negro” or “Black” instead of the common term “Negro,” had a profound impact on the growing sense of racial pride which would emerge profoundly during the Black Power movement decades later. But, as Malcolm X explained to a college audience: “We call ourselves Muslim – we don’t call ourselves Black Muslims. This is what the newspapers call us . . . We are Muslims. Black, brown, red, and yellow.”8 In other words, the Nation of Islam saw itself as firmly within both a world community of Islam as well as in solidarity with other people of color around the world.

Cassius Clay was born in 1942 in Louisville’s racially segregated Parkland neighborhood. Several months later, Japanese forces began an attack on U.S. and Filipino troops in the providence of Bataan in the Philippines. That some month, a window washer for the Department of Agriculture, stood before a judge for not registering with the selective service. Joseph X Nipper explained that he was “on the side of our nation Islam, which is composed of the dark peoples of the earth, consisting of the black, brown, red and yellow people.” Benjamin Mitchell, a carpenter with the Public Buildings Administration, claimed to be “registered with Islam.”9 The men were part of a group of fifty Muslims who pledged fealty to the Nation of Islam during World War II in solidarity with Japan. Of 73 total cases of draft resistance by African Americans, almost three-quarters were part of the NOI. The FBI, believing this stand had to do with ethnic heritage, knowingly commented that although the group’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, “is a Georgia negroe [sic], he looks like a Japanese, having slant eyes.”10

During the Korean War, the Nation of Islam again aligned itself with its “Asiatic” brothers. A young incarcerated Malcolm X wrote to President Harry Truman that he had “tried to enlist in the Japanese Army, last war, [and] now they will never draft or accept me in the U.S. Army.”11 The letter, in which Malcolm identified himself as Communist, prompted the Bureau to begin its intensive decade-long surveillance file on the NOI minister. Just a year after his release, Malcolm X was approached at his factory job in Wayne, Michigan and asked by an FBI agent why he had neglected to register for the Korean War draft. Malcolm answered a questionnaire by filling in the blank: “I am a citizen of _____” with “Asia.”12

In 1960, Elijah Muhammad’s son Wallace was sentenced to prison for his failure to register with the selective service. He ultimately chose to serve a three-year sentence at a federal prison in Sandstone, Minnesota rather than report to Illinois’ Elgin State Hospital where he believed that serving the hospital would aid the war effort. By the end of the Vietnam War, nearly one hundred Muslims in the NOI had served prison sentences for draft evasion. While Muhammad Ali’s decision to refuse induction in 1967 represented the most public expression of draft resistance, it fit firmly within the Nation of Islam’s long history of Third World solidarity and anticolonialism, one in place since his birth in 1942.

It is perhaps not surprising that Muhammad Ali’s draft resistance and solidarity with the North Vietnamese has been severed from the Nation of Islam’s long history of draft resistance. A parallel narrative exists for Malcolm X. Despite spending almost the entirety of his public life as national spokesman for the NOI, Malcolm is often framed independent from the group – as too political, too religiously orthodox, or both. However, to de-Islamicize Muhammad Ali in our current moment of rampant Islamophobia and make him a sanitized American hero does several forms of historical violence. First, it diminishes the role of black political and religious movements, specifically black nationalism and Islam, in the American public sphere. The Nation of Islam was at the vanguard of the antiwar movement, critiquing a once-popular conflict (in 1966, only 11% of Americans favored pulling out of Vietnam) which is now considered as a war of capitalism and conquest. Secondly, it buries an expression of politicized Islam which radically and peacefully critiqued American imperialism and foreign policy. Finally, it cleaves a charismatic and exceptional figure from the historical context which nevertheless produced him. We cannot expect future generations to make similar brave and resolute challenges without understanding that Ali did not act alone. For his decision to not fight another “Asiatic people” was born out of decades of resistance, imprisonment, and legal challenges by other “Asiatics” – from Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X to Joseph Nipper and Benjamin Mitchell.

- He had been classified I-Y for a low IQ score in 1964. ↩

- Robert Lipsyte, “Clay Reclassified 1-A by Draft Board,” New York Times, February 18, 1966. ↩

- David Remnick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero (New York: Random House, 1998), 287. ↩

- Daniel Lucks, Selma to Saigon: The Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 7. ↩

- “Northern Ireland Fits ‘Third World’ Category,” Muhammad Speaks, February 25, 1971. ↩

- See Elliott J. Gorn, editor. Muhammad Ali: The People’s Champ (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995), 45. ↩

- Jeffrey Sammons, “Rebel with a Cause: Muhammad Ali as Sixties Protest Symbol,” ibid., 170. ↩

- Malcolm X, “Twenty Million Black People in a Political, Economic, and Mental Prison,” January 23, 1963, in Malcolm X: The Last Speeches, ed. Bruce Perry (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1989), 51. ↩

- “Moslem Says He ‘Registered with Islam,” Washington Post, August 2, 1942. ↩

- Karl Evanzz, The Messenger: The Rise and Fall of Elijah Muhammad (New York: Pantheon Books, 1999), 137. ↩

- Malcolm X FBI File, Summary Report, May 4, 1953, 3. ↩

- Louis DeCaro Jr., On The Side of My People (New York: New York University Press, 1996), 97. ↩

I love this essay’s astute critique of the de-politicalization of Muhammad Ali. Thank you!

Thank you Mark!