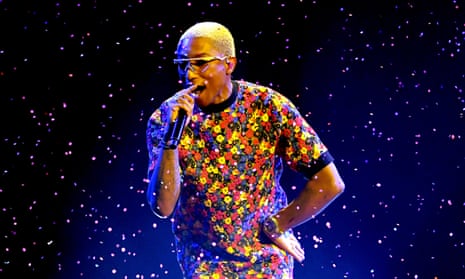

Incensed by Donald Trump’s use of his 2013 song Happy at a rally in Indiana on Saturday, Pharrell Williams has threatened legal action against the president. In a cease-and-desist letter sent by Williams’ lawyer, the demand specifically took umbrage at the use of the song for political purposes just hours after a shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue.

“On the day of the mass murder of 11 human beings at the hands of a deranged ‘nationalist’, you played his song Happy to a crowd at a political event in Indiana,” the letter said. “There was nothing ‘happy’ about the tragedy inflicted upon our country on Saturday and no permission was granted for your use of this song for this purpose.”

Williams joins a lengthy list of artists who have asked politicians, most frequently conservatives, to stop using their music. Abba asked John McCain to stop playing Take a Chance on Me during his run for the presidency, while the Dropkick Murphys were more characteristically blunt when Wisconsin’s governor, Scott Walker, took the stage to their Shipping Up to Boston.

@ScottWalker @GovWalker please stop using our music in any way...we literally hate you !!!

— Dropkick Murphys (@DropkickMurphys) January 25, 2015

Love, Dropkick Murphys

Bands protesting against politicians is nothing new, but the lineup of musicians who have asked Trump to stop playing their songs alone is a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on its own.

Trump ends almost every rally with the Rolling Stones song You Can’t Always Get What You Want. The band has repeatedly ask Trump to stop playing their music, but so far have had no success in getting him to do so.

Neil Young, who also asked the campaign to refrain from playing Rockin’ in the Free World, eventually relented, saying: “Once the music goes out, everybody can use it for anything.”

Barbra Streisand's music is used to pump up the crowd at MAGA rallies. "I’m just so saddened by this thing happening to our country. It’s making me fat. I hear what he said now, and I have to go eat pancakes now, and pancakes are very fattening." https://t.co/nBONQBfjpp

— Katie Rogers (@katierogers) October 30, 2018

Michael Stipe of REM voiced his distaste for Trump a bit more directly after the band’s It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine) – which critics might think is a fitting choice for the administration – was used in 2015 at a campaign stop.

“Go fuck yourselves, the lot of you – you sad, attention-grabbing, power-hungry little men. Do not use our music or my voice for your moronic charade of a campaign,” Stipe responded.

Adele likewise made it clear she did not give permission to the campaign to use her music in 2016.

The scene in WV before Trump’s rally. Aerosmith’s “Livin’ on the edge” playing. pic.twitter.com/HW1qr9TBgE

— Jim Acosta (@Acosta) August 21, 2018

This summer, Steven Tyler of Aerosmith sent a cease-and-desist of his own, objecting to the use of Livin’ on the Edge at a campaign rally, following a similar complaint three years earlier that the campaign ignored.

“By using Livin’ On The Edge without our client’s permission, Mr Trump is falsely implying that our client, once again, endorses his campaign and/or his presidency, as evidenced by actual confusion seen from the reactions of our client’s fans all over social media,” the letter said.

“This specifically violates Section 43 of the Lanham Act, as it ‘is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person’.”

The Lanham Act refers to “the confusion or dilution of a trademark (such as a band or artist name) through its unauthorized use”, Ascap, one of the major publishing groups, explains.

The confusion stoked by politicians’ use of music for political purposes carries over into the question of whether artists can actually do anything about it. Often in the case of campaign rallies held in the type of venues where Trump appears, there will be an overarching license through the major publishing companies that allow for the use of songs, said Gandhar Savur, senior vice-president for legal affairs at Rough Trade Publishing.

“If the venue that is holding a political rally has a ‘performance rights organization’ blanket license in place, such as, for example, through Ascap or BMI, then a politician can get away with having a particular song playing in the background.”

However, if the song becomes a regular soundtrack for a particular politician, that might give the artist, label or publisher, more leverage to stop them.

“This is largely unsettled law, and has definitely come to the forefront with the current administration, but the common way to attack repeated use of a song by a politician is to make a right of publicity claim,” Savur said.

Generally speaking, rights of publicity, under state law, protect individuals from having their likenesses, including their voices, used in connection with a commercial purpose, “which can include exploitative and promotional uses”.

“Artists would argue that the politician is creating a ‘false endorsement’, ie giving the public the false impression that the artist endorses that politician or his or her campaign, by the repeated use of their song and voice,” Savur said.

Often a politician will simply comply with the request because the negative attention from a popular band is more trouble than continuing to play a song is worth. But as with everything else, Trump seems to be playing by his own rules. He still finishes almost every rally with You Can’t Always Get What You Want.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion